BIBLE HISTORY & TRANSLATIONS

Download BIBLE HISTORY & TRANSLATIONS

BIBLE HISTORY AND TRANSLATIONS

The Download version is generally the latest version and has updated charts.

OLD TESTAMENT (OT)

The Tanakh, also called the Hebrew Canon, is the sacred text of Judaism, comprising the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings—the Hebrew Scriptures from which the Old Testament (OT) is derived. "Testament" refers to "Covenant," specifically the old covenant God made with His people. The Hebrew Canon is considered the "measuring stick," meaning these are the scrolls deemed as the "inspired Word of God."

Is there an original script from the authors?

No, we do not have the original manuscripts written by the biblical authors. Only handmade copies exist, and while these copies sometimes differ slightly, the differences are typically minor (e.g., spelling or word order) and do not impact major doctrines.

What is the Hebrew Canon?

The Hebrew Canon is the collection of authoritative scrolls that make up the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). "Canon" means "measuring stick," used to select the inspired books of God's Word. The Hebrew Canon was compiled gradually between 400 BC and 200 BC, and Jewish rabbis translated these texts into Greek in the Septuagint (285 BC), which also included additional books not in the Hebrew Canon. The last book of the Canon, Malachi, was written around 430 BC.

- Law (Torah): The Canon, including Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, was recognized as the foundation around 1400 BC and served as the basis for determining future prophets and God's authoritative Word.

- Prophets: The writings of the prophets were compiled and canonized around 200 BC. divided into the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings), the Latter Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel), and the Minor Prophets (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi).

- Writings: The canonization of the Writings occurred around 90 AD at the Council of Jamnia, where the final decisions on the Hebrew Bible's authoritative books were discussed. These writings were added to the already recognized Law and Prophets, forming the Masoretic Text. This included Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ruth, Song of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles.

The Bible contains 39 books in the Old Testament because some books (e.g., 1 & 2 Kings) are split into two parts, and the Minor Prophets are each counted individually, while in the Hebrew Canon, they are grouped together as one book. Thus, the Hebrew Canon aligns with the Old Testament in the Christian Bible today.

When were the various books compiled?

Job (~1900 BC), The Law: Genesis (1445 BC), Exodus (1445 BC), Leviticus (1445 BC), Numbers (1410 BC), Deuteronomy (1406 BC), Joshua (1375 BC), Judges (1050-1100 BC), Ruth (1050 BC), 1 & 2 Samuel (722-931 BC), Proverbs (950-720 BC), Ecclesiastes (931 BC), Song of Solomon (930-970 BC), Isaiah (690-700 BC), Joel (805-835 BC), Jonah (760 BC), Nahum (612 BC), Hosea (750 BC), Amos (750-760 BC), Daniel (582-605 BC), Micah (696-704 BC), Zephaniah (630 BC), Habakkuk (600 BC), Ezekiel (573-593 BC), Jeremiah (586-626 BC), Lamentations (587 BC), Haggai (520 BC), Obadiah (586 BC), 1 & 2 Kings (538-560 BC), Esther (465 BC), Ezra (538-457 BC), Nehemiah (423 BC), Malachi (450 BC), Zechariah (475-520 BC), 1 & 2 Chronicles (450 BC).

Any differences between the Tanak (Jewish Bible) and the Christian Old Testament?

The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and the Old Testament (OT) differ in organization and book count:

Number of Books: The Tanakh has 24 books, while the Christian OT has 39. This difference is due to grouping: In the Tanakh, books like 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings, and 1 & 2 Chronicles are counted as one book each, while the OT splits them into two. The Minor Prophets are one book in the Tanakh but are counted separately in the OT. Order of Books:

- The Tanakh is divided into three sections: Torah (Law), Nevi'im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings).

- The OT follows a different order, starting with the Pentateuch, followed by Historical Books, Wisdom Literature, and Prophets.

What was the original language?

The Hebrew Canon was primarily written in Hebrew, with parts of the Old Testament in Aramaic. Aramaic was widely spoken in the Near East, especially during the Babylonian and Persian empires. Jesus spoke Aramaic, and it was used in Assyrian diplomacy.

Aramaic appears in several parts of the Old Testament, including 2 Kings 18:26, Isaiah 36:11, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4-7:28, Ezra 4:8-6:18, and Ezra 7:12-16. Aramaic is distinct from Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia.

What criteria did God give His people in discovering the Hebrew Canon?

God provided the Torah through Moses as the initial “measuring stick” for evaluating other writings. The criteria for determining the Hebrew Canon can be seen by comparing the included texts with those that didn’t make it.

- Authorship: Was the scroll written by a prophet or man of God, confirmed by God's actions (prophecies fulfilled or divine insight)?

- Confirmation: Did other prophets or men of God affirm the writings?

- Alignment with the Torah: Did it align with God’s laws (the first five books)? If not, it was excluded.

- Redemptive Message: Did it support the Torah’s theme of redemption and transformation of lives to bring people back to God? Jesus referenced this in Luke 24:44: "These are the words I spoke to you... that all things must be fulfilled... in the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms about Me."

Only those writings that met these criteria were considered Holy Scripture, inspired by God.

All Hebrew Manuscripts

|

Manuscripts |

Manuscript Date |

Contents |

Comments |

|

Dead Sea Scrolls |

150BC - 70AD |

Torah, Prophets, Writings, Pseudepigrapha, Sect and Secular writings |

Every book of the Tanach/Old Testament has been found, at least in part, with the exception of the book of Esther. Other books were discovered as well including secular writings and some pseudepigrapha. |

|

Cairo Geniza Fragments |

500AD - 800AD |

|

|

|

Ashkar‑Gilson |

600-700AD |

Partial Exodus |

|

|

Cairo Codex |

895AD |

Prophets, Writings |

|

|

Leningrad Codex |

916AD |

Prophets |

One of the ben Asher Masoretic manuscripts |

|

Aleppo Codex |

930AD |

Torah, Prophets, Writings |

The Aleppo Codex, a ben Asher Masoretic manuscript, served as a source for the Hebrew University Bible and Maimonides' Torah Scrolls. Written by Shelomo ben Baya’a and pointed by Moses ben Asher (930 AD), it was thought to be destroyed in a 1948 fire. However, only the Torah portion was lost, and the remaining books were saved. Smuggled from Syria to Israel, the codex has been photographed and will be the basis for the New Hebrew Bible published by the Hebrew University under the ben Asher family's authority. |

|

British Museum Codex |

950AD |

Torah (incomplete) |

|

|

Leningrad Codex |

1008AD |

Torah, Prophets, Writings |

One of the ben Asher Masoretic manuscripts. Most modern manuscripts based on this text |

|

Kitag Gi-Hulaf |

Before 1050AD |

Torah, Prophets, Writings |

The earliest extant attempt at collating the differences between the ben Asher and ben Naphtali Masoretic traditions was made by Mishael ben Uzziel. |

|

Abisha Scroll |

1200AD |

Torah |

While tradition dates its origin ~1400 BC, the oldest surviving physical copies are AD 1200. |

|

Reuchlin Codex |

1105AD |

Prophets |

|

|

Codex Nablus |

1211AD |

Torah |

Samaritan Hebrew Text |

|

First Rabbinic Bible/ Ben Chayyim |

1524AD |

Torah, Prophets, Writings |

Composed by Daniel Bomberg; second edition composed by converted Rabbi Abraham ben Chayyim; The KJV is based on this text. |

|

Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia |

1906AD |

Torah, Prophets, Writings |

Composed by Rudolph Kittel and revised in 1912; Based on the ben Chayyim text. Revised again in 1937 but based on the Codex Leningrad (Ben Asher); this was then revised in 1966-68. |

Earliest Manuscripts – prior 6th Century

Septuagint Version (285 BC) - Koine Greek

The Septuagint (LXX), the first translation of the Old Testament, was created around 300 BC when Alexander the Great’s empire expanded eastward. The Egyptian King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-247 BC), interested in Jewish scripture, commissioned 72 Jewish translators to translate the Hebrew Pentateuch into Greek for his library in Alexandria. The LXX became the Bible of the early church, and its order of books influenced the Vulgate, later translated by Jerome.

The translation varied in accuracy due to the lack of a standardized translation method, leading to ongoing revisions. The LXX included 35 additional books (called the Apocrypha), written in Greek and not accepted by Jews as inspired Scripture, thus excluded from the Tanakh. The oldest known LXX manuscript dates to 350 AD.

Before Christ, other translations such as the Syriac and Samaritan versions also existed, with the LXX being the most widely used by Hellenistic Jews who no longer knew Hebrew. Early Christian writers occasionally quoted from the LXX, though they sometimes translated directly from the Hebrew. Despite its uneven quality, the Septuagint had a significant impact on the early Gentile church.

Dead Sea Scrolls (150BC - 70AD) - Hebrew

They were discovered between 1947-56 in the Qumran caves near the Dead Sea. These ancient manuscripts, dating from 150 BC - 68 AD, include a diverse range of texts such as religious writings, biblical manuscripts, and community rules. They are the oldest known manuscripts containing portions of every Old Testament book, including an almost complete copy of Isaiah, with the exception of the Book of Esther. Recent studies suggest that some fragments may come from a proto- or variant form of Esther.

The scrolls were written in Hebrew and Aramaic. Originally, they were composed without vowels, which posed little difficulty for fluent Hebrew readers, who could deduce the correct words from context. 6th century AD, the Masoretes added vowel points to the text to standardize pronunciation.

The discovery began in March 1947 when a young Arab boy found jars containing leather manuscripts in the Qumran caves. These manuscripts belonged to the Essenes, a Jewish sect that had settled in the Judean desert. Over the next decade, additional manuscripts were found, including two copies of Isaiah and fragments from nearly every Old Testament book, except for Esther. The Dead Sea Scrolls are owned by the State of Israel.

Onkelos Targum (AD 1-200) – Aramaic

A literal translation of Genesis to Deuteronomy from Hebrew into Aramaic. The oldest extant copy dates to 400-600 AD. The English translation, based on the 1482 Bologna edition, was published in 1862.

Jonathan Targum (AD 100-200) – Aramaic

Judges to 2 Kings and Isaiah to Malachi (except Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah).

Palestinian Targum (AD 200-400)

A paraphrased translation of Genesis to Malachi (except Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah).

Peshitta Old Testament (~150 AD, oldest copy 5th Century) - Aramaic

Direct translated from the Hebrew text of that time (not from the Septuagint), making it similar to the Masoretic Text. As a result, it predates the finalized Masoretic Text, which was standardized in the medieval period.

Neofiti Targum of the Torah (AD 300-400)

A paraphrased translation Genesis to Deuteronomy, with some later copies extending to the 14th century.

Pseudo-Jonathan & Jerusalem Targum (TPsJ) of the Torah (AD 300-400, oldest copies 10th Century):

A paraphrased translation of the first five books. Dating from the 4th century (some sources date it to the 12th century), the English translation is based on the 1591 Venice print edition.

Side Note: Targum means “translation” or “interpreter”. Targums were translations of the Hebrew Scriptures into Aramaic. When the Hebrew Bible was read, a translator would interpret it into Aramaic for the listeners.

Abisha Scroll (500AD-1100AD) - Hebrew

The Abisha Scroll, traditionally attributed to Abishua (great-grandson of Aaron), is the foundational manuscript of the Samaritan Pentateuch. While tradition dates its origin over 3,000 years ago, the oldest surviving physical copies are ~ 12th century AD, preserved by the Samaritan community in Nablus. The Samaritan text tradition may be much older, but no earlier manuscripts survive. A similarly named scroll in Ethiopia is linked to local legend rather than historical fact.

How was the Hebrew Text (Masoretic Text - MT) copied through the centuries?

Only scribes were allowed to make copies, and they had extremely strict guidelines to follow when copying the original text.

- They had to be isolated;

- They needed to take ritual baths before starting;

- They were required to follow God's ordinances (including sacrifices and observing the festivals);

- They could not copy it from memory; they had to speak it aloud and then write it down;

- Every time they wrote the name of God, they would wipe their pen;

- After completing a scroll, they would count the words and letters to ensure there were no mistakes. This system was called the Massorah.

The Massorah was written in the margins of the Holy Scriptures and included, among other things, a count of the number of times an individual letter appeared on a page. It also specified the exact letter, word, and sentence that should appear in the center of the page. By using this system, a scribe could check their work and ensure that no letter was missed or repeated. This method was inspired by Almighty God and helped ensure that the sacred texts remained error-free.

Because the texts were written on continuous scrolls made from animal skin, any mistake could not be crossed out. Instead, the scribe would have to discard the skin and start over. This illustrates the level of accuracy required when copying the original text. Every stroke had to be precise, as later evidenced when comparing the Dead Sea Scrolls to earlier Hebrew writings, which were separated by 1,000 years. The only differences found were in the pen strokes and the introduction of vowels.

The Masoretic Text (MT) is the Hebrew text of the Tanakh, which is the version approved for general use in Judaism. It is also widely used in translations of the Old Testament in the Christian Bible. The scribes of the 6th century, known as the Masoretes, continued to preserve the sacred Scriptures for another 500 years, leading to the development of the Masoretic Text (MT). The main centers of Masoretic activity were Babylonia, Palestine, and Tiberias. By the 10th century AD, the Masoretes of Tiberias, led by the ben Asher family (Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, who died in 960 AD), gained prominence. His father, Moses ben Asher, is credited with writing the Cairo Codex of the Prophets (895 AD), one of the oldest surviving manuscripts containing a large portion of the Hebrew Bible. Another significant manuscript of the Masoretic Text is the Aleppo Codex (900 AD), which is believed to predate the Leningrad Codex (1008 AD).

Aaron ben Asher himself added vowels and cantillation notes to the text (e.g., Leningrad Text). He lived and worked in Tiberias on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. By the 12th century, through subsequent editions, the ben Asher text became the only recognized form of the Hebrew Scriptures.

In 1516-17 AD, Daniel Bomberg printed the first Rabbinic Book, followed by a second edition in 1525 AD, prepared by Jacob ben Chayyim (ben Chayyim/Hayyim Text) and also published by Bomberg. This edition was based on the most reliable text of the time. Jacob ben Chayyim, a Jewish refugee who later converted to Christianity, is considered an “apostate” by many Jews, and his text is often rejected by rabbis today. However, his text was used by Jews until the 20th century. This second edition was adopted in most subsequent Hebrew Bibles, including those used by the King James translators, and was also used for the first two editions of Rudolph Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica (BHK) in 1906 and 1912.

In 1937, Paul Kahle published a third edition of the Biblia Hebraica, based on the oldest dated manuscript of the ben Asher Leningrad Manuscript (1008 AD), which Kahle regarded as superior to the ben Chayyim text due to its greater age. The Stuttgart edition of Biblia Hebraica (BHS), published between 1968 and 1977, is the edition now used in modern translations.

Which Hebrew texts are primarily used in English translations?

Translators primarily use the ben Asher Leningrad Codex (1008 AD), the most complete and widely accepted manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. Some early translations, such as the King James Version, relied on the ben Chayyim Text (1525 AD), but today the Leningrad Codex and editions based on it, like the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), are more commonly used in modern translations.

Which is more accurate source text for the English Translation - Hebrew Text ben Asher (1008AD) or ben Chayyim (1525AD) or BHS (1964-66)?

While it is said that there are 20,000-30,000 differences between the texts, most do not significantly affect the overall meaning, except for a few key cases. There are more differences when comparing the Ben Asher to the BHS than when comparing the Ben Chayyim.

The Ben Chayyim is more accurate, as this was the primary Hebrew text used for translations from 1525 AD until the early 20th century (1937 AD). Some believed that the Ben Asher was available in the 1500s but was not used due to potential discrepancies. Thus, the Ben Chayyim was widely adopted by both rabbis and Christian translators for 400 years. Then for a short time (30years) ben Asher was used until 1964 when BHS was considered the leading text (for the last 80 years). The BHS became the central text used for most modern translations (ESV, CJB, NIV, etc.). But overall, the differences are insignificant compared to the New Testament source text RT vs CT.

A couple of significant differences between ben Asher and ben Chayyim:

- The Ben Chayyim text uses two different spellings of the Tetragrammaton "YHWH," while the Ben Asher text has six different spellings, with the Ben Chayyim being more consistent.

A couple of significant differences between ben Chayyim and BHS:

- 1 Sam 13:1 Ben Chayyim “Saul reigned one year; and when he had reigned two years over Israel” vs. “Saul was … years old when he began to reign, and he reigned … and two years over Israel”.

- Ezekiel 11:19 Ben Chayyim “and I will put a new spirit within you” vs. BHS “and a new spirit I will put within them.”

See the chart below.

What is the Apocrypha and is it inspired by God?

The term "Apocrypha" comes from the Greek apokryphos, meaning "hidden away." The word "apocryphal" generally refers to writings whose authenticity or divine inspiration is uncertain. The Apocrypha refers to a collection of books that were not included in the Jewish canon of the Hebrew Bible but were included in some early Christian Bibles, particularly the Septuagint. These books are often seen as supplemental and are not considered divinely inspired by most Jewish traditions, although they were read and valued by some early Jewish and Christian communities. For example, the 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus mentioned them, though he did not consider them as sacred as the canonical Scriptures.

The Apocrypha includes books that were written during both the Old Testament (pre-30 AD) and New Testament (post-31 AD) eras. Many of these books were part of the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures that became widely used by early Christians.

Apocryphal Books:

Some of the commonly recognized Apocryphal books include Tobit (250-180 BC), the Letter of Jeremiah / Baruch 6 (200 BC), the Prayer of Azariah ("Song of the Three Holy Children") following Daniel 3:23 (200-160 BC), 1 Esdras (300-150 BC), the Prayer of Manasseh (150 BC), Judith (150 BC), Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) (150-100 BC), Additions to Esther (130 BC), Susanna / Daniel 13 (100 BC), 1 Maccabees (90-70 BC), 2 Maccabees (50 BC - 100 AD), Baruch (70-100 AD), 2 Esdras (100 AD), Ecclesiasticus / Sirach (32 BC - 180 AD), and the Wisdom of Solomon (30 BC - 40 AD).

What is the Pseudepigrapha?

The Pseudepigrapha refers to a collection of ancient texts that are falsely attributed to famous figures or biblical characters, such as prophets or important religious leaders. These works claim to have been written by a notable figure from the past, but their true authorship is uncertain or from a much later time. For example, the Book of Enoch is attributed to the biblical figure Enoch, but scholars believe it was written centuries after his time. These works are not considered part of the biblical canon, except in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, where it is part of the Biblical canon. I personally believe it is part of the canon.

Why Aren’t the Apocrypha Included in the Hebrew Canon (OT)? 8 Fundamental Reasons

- Jewish Criteria: The Apocrypha was not included in any lists of inspired books until over 300 years after Christ, and even then, only a few were added. At the Council of Jamnia in 90 AD, where the Hebrew Scriptures were canonized, the rabbis rejected the Apocrypha as inspired and excluded them from the Jewish canon. This exclusion was consistent with long-standing Jewish tradition, which did not regard the Apocryphal books as Scripture.

- Josephus’ Exclusion: Josephus (30-100 AD), a Jewish historian, explicitly excluded the Apocrypha from the Jewish canon, listing only 22 books as authoritative. He also never quoted the Apocryphal books as Scripture. Josephus famously wrote: “We have not an innumerable multitude of books among us, disagreeing from and contradicting one another, but only twenty-two books, which contain the records of all the past times; which are justly believed to be divine...” (Against Apion 1:8). This was in line with Jewish thought at the time of Jesus, emphasizing the belief that the canon was complete and that later writings, like the Apocrypha, did not hold the same divine authority.

- No Claims to Inspiration: Not one of the writers of the Apocryphal books lays any claim to divine inspiration. For example, in 2 Maccabees 2:24-32, it is stated that there was no prophet in Israel at the time. Additionally, 1 Maccabees 4:46 states that they were awaiting a prophet to offer divine answers. This reflects the general understanding in the Apocryphal books that they did not possess the same inspired authority as the canonical Scriptures.

- Contradictions and Doctrinal Issues: Many of the Apocryphal books contain theological inconsistencies, contradictions with the Torah, and teachings that are incompatible with later biblical revelation. For example, the doctrine of prayers for the dead (2 Maccabees 12:39-46) and statements that contradict the Bible, such as those in Ecclesiasticus 25:19 and 25:24 blaming women for sin, are viewed as heretical. Additionally, the Apocrypha contains teachings that promote practices opposed to the Torah, like lying, suicide, and magical incantations.

- Jesus and New Testament Writers' Silence: Jesus and the New Testament writers never quoted from the Apocrypha, despite quoting extensively from the Old Testament. Some argue that books like Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon are also not quoted in the New Testament. However, these books were always recognized within their respective collections (History or Poetry), and quoting one book from a collection verifies the authority of the entire collection. The Apocrypha, however, was not universally accepted, as evidenced by its lack of New Testament quotations.

- Early Church Fathers' Rejection: Several early Christian leaders, including Origen, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Athanasius, rejected the Apocrypha as canonical. While some early church writings did reference the Apocrypha, these books were not regarded as Scripture by the majority of early Christian leaders. For example, Origen (185-254 AD) and Melito of Sardis (170 AD) did not accept the Apocrypha as canonical.

- Jerome’s Position: Pope Damasus (AD 366-384) commissioned Jerome to translate the Bible into Latin (the Latin Vulgate). Jerome initially rejected the Apocrypha, but under pressure from Pope Damasus, he eventually included some of the Apocryphal books in the Vulgate, though he placed them in a separate section. Jerome referred to the Apocrypha as “books of dubious authenticity.” Later, the Apocryphal books were added by others, but Jerome’s initial hesitation shows that they were not universally accepted as canonical by early Christians.

- The Council of Trent (1546 AD): The Apocryphal books were officially declared canonical by the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Trent in 1546 AD. This decision was largely a response to the Protestant Reformation, particularly the challenges posed by figures like Martin Luther, who rejected the Apocrypha due to doctrinal differences. The Catholic Church’s decision to include the Apocrypha in the canon was partly driven by the theological support these books provided for certain Catholic doctrines. Prior to the Council of Trent, the Apocrypha had not been regarded as canonical in the Church.

NEW TESTAMENT (NT)?

What is the New Testament (NT)?

The term "New Testament" (NT) refers to the "New Covenant" that God established with mankind through Jesus Christ, and it explores its implications. The NT focuses on the life, teachings, and redemptive work of the Messiah, Jesus Christ of Nazareth. It is called the Greek Canon because the books were written in Koine Greek under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Some scholars believe Matthew might have originally written his Gospel in Aramaic, but Greek was the common language of the time, much like English is today. It was spoken across a broad region, from Israel to Russia and other surrounding areas. Although primarily written in Greek, the NT also includes several Aramaic words and phrases, which were incorporated into Greek. Jesus himself spoke Aramaic, and some of those words have been preserved, such as “Talitha, cumi,” meaning "Little girl, arise" (Mark 5:41).

Up until the 10th century, Greek manuscripts were written entirely in uppercase letters, known as Uncials (large hand). From the 9th to 15th centuries, a new lowercase script called Minuscules (or Cursive) gradually replaced the older Uncial style.

The Greek Canon is a collection of 27 authoritative books, divided into the following parts:

- Gospels (Four accounts of Jesus Christ’s life from different perspectives)

- Acts (The story of the early church)

- Epistles (Letters written to specific individuals and churches in various regions)

- Revelation (God’s redemptive plan and its final fulfillment)

How could the Gospel writers have remembered so many details after so many years?

- Jesus' words had a profound impact on people, and His unique storytelling style would have been unforgettable. The Jewish people were also accustomed to memorizing large texts because scrolls were expensive to own, unlike today.

- In concentration camps, some people memorized the entire New Testament to preserve it. Many also memorized the Gospels. Today, there are theatrical performances where people recite the Gospels word-for-word. So, it’s likely the disciples memorized Jesus' words too.

- Matthew, being a tax collector, was skilled in shorthand, which could have helped in recording details.

- The disciples might have also kept personal notes during their time with Jesus.

- The Holy Spirit was present within them, reminding them of Jesus' teachings, just as He promised.

What’s even more remarkable is that the four Gospels align perfectly. In a court of law, if two witnesses give the same testimony, it is considered true. How much more compelling is it that four different people, writing from different locations, reported the exact same events? This is truly extraordinary. Furthermore, the Torah, Writings, Psalms, and Prophets all support the Gospels, without any contradictions. This can only be explained by divine intervention, confirming that the Scriptures were inspired by God Himself.

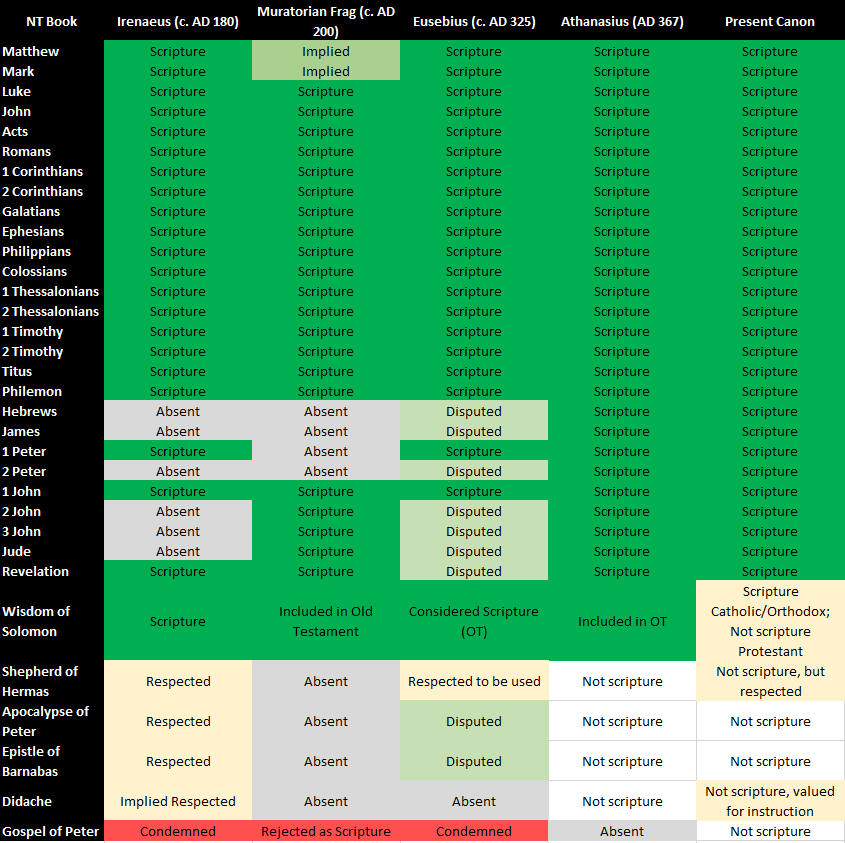

Who Decided Which Books Are in the Greek Canon We Have Today?

The New Testament (NT) is a collection of authoritative writings composed over approximately 55 years (from around 40-95 AD), while the events they describe occurred between 4 BC–69 AD. The NT also includes prophecies and teachings that span from creation to eternity.

By 50-100 AD, 23 of the 27 books of the NT were already in use by Christian communities in Jerusalem, Antioch, Rome, and Alexandria. By around 170 AD, the full 27 books were being used by some Christian groups, such as those in the Syriac-speaking regions (e.g., the Peshitta, which included all 27 books).

Irenaeus of Lyon does not clearly cite James, Hebrews, 2 Peter, or 3 John, though this does not mean those books were unknown or not circulating. Although many manuscripts circulated in the 1st to 3rd centuries, these manuscripts were compiled by editors like Lucian (250-312 AD), who helped standardize the texts.

The first complete list of the 27 New Testament books as we have them today appears in Athanasius’s Festal Letter (AD 367), which includes James, Hebrews, 2 Peter, 3 Peter. The Festal Letter announced the dates of important Christian feasts, especially the Passover (“Easter” to some).

Council of Nicaea - There is no historical evidence that the Council of Nicaea addressed the New Testament canon at all. We possess the surviving records of the council, and canon formation is not among its topics. Constantine did not determine the canon, and while he called for the council, he did not exercise theological authority over its decisions--- so they say. The main issues discussed at Nicaea concerned doctrine (the Arian controversy - the nature of Christ) and Tradition, such as which day "Passover" should be celebrated.

What Criteria Did God Provide for Determining the Greek Canon?

Hebrews 1:1-2: “God, who at various times and in various ways spoke in time past to the fathers by the prophets, has in these last days spoken to us by His Son, whom He has appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the worlds.” Therefore, there was no formal document providing the criteria but by reviewing the selected books we can identify the criteria indirectly used. Books were included if they were written by Jesus' half-brothers, His apostles or by those associated with them, or those they approved. For example:

- Jude and James both half-brothers of Yeshua (Matt. 13:55; Gal 1:19; Jude 1:1; Eusebius quotes Papias in Ecclesiastical History 3.39.).

- Peter and John were Apostles.

- Paul, received the “right hand of fellowship” from Peter (2 Pet. 3:15-16), James, and John (Gal. 2:9).

- Mark was Peter’s interpreter and scribe (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 3.39). Luke was Paul’s companion (Col. 4:14).

By the time of Irenaeus of Lyon (~AD 180), most of the New Testament (NT) books were already in circulation. Irenaeus affirmed the four Gospels, Acts, most of Paul’s letters, 1 Peter, 1 John, and Revelation, attributing it to the apostle John - not an elder or another person.

What about NT apocryphal books?

The NT Apocryphal books did not carry any authority even back then, as many of these books were written after 100 AD. Furthermore, they were not written by the disciples, the brothers of Jesus, nor by those whom the disciples, like Paul, acknowledged as authoritative. These books were mostly written by "Christians" and some by Gnostics. As a result, they were removed after 367 AD.

Any Original Greek Text Written by the Author?

No, there are Greek manuscript of the NT written by the authors. Each of the NT books were written individually and copies were distributed among the early Christian communities. Many manuscripts have been discovered in various parts of the Greek-speaking world, with some found in Alexandria, Egypt. However, some of these manuscripts are considered less reliable because they reflect influences from Gnostic and heretical teachings, leading to contradictions in the text.

If we don’t have the originals, how can we trust the copies?

While we don’t have the original manuscripts of the New Testament, we have over 24,000 copies and fragments in various languages, allowing for extensive comparison. The more manuscripts we have, the better we can confirm the accuracy of the text. Variations are mostly minor, like spelling differences or word order, and don’t affect core teachings.

What Are the Oldest NT Greek Manuscripts or Fragments?

FRAGMENTS

|

|

7Q O'Callaghan 60-100AD. (7Q means 7th Cave of Qumran) In 1972, José O'Callaghan identified 7Q5 from Cave 7 as potentially corresponding to Mark 6:52-53, dated to 60-100 AD. However, this identification is debated due to the fragment’s condition and dating uncertainties. Other fragments have been linked to verses such as:

However, these identifications are speculative, as the fragments are incomplete and open to interpretation. Many scholars caution against definitively linking them to the New Testament. |

|

|

The John Rylands Fragment (P52), (125 AD) This papyrus codex contains portions of John 18:31-33 and 37-38. Written on both sides, it is one of the earliest known papyrus manuscripts of the New Testament. Found in Egypt, far from its place of origin (Asia Minor), it illustrates the early transmission of the Gospel. The fragment is housed in the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. |

|

|

Magdalen Papyrus (P64) (~200 AD) The Magdalen Papyrus, consisting of scraps housed at Magdalen College for over 90 years, was a gift from British chaplain Rev. Charles Huleatt, who acquired them in Luxor, Egypt. Originally dated to the mid- to late 2nd century, new analysis using scanning laser microscopy and handwriting comparison re-dated the fragments to before 66 AD. The papyrus contains portions of Matthew 26:7-8, 10, 14-15, 22-23, 31-33. In three places, "Jesus" is abbreviated as "KS" (Kyrios, meaning Lord). Some scholars believe P64, P4, and P67 are part of the same document. |

|

|

P67 (~200AD) Gospel of Matthew (3:9, 15; 5:20-22, 25-28) |

|

|

P4 (~200AD) Luke (1:58-59; 1:62-2:1, 6-7; 3:8-4:2, 29-32, 34-35; 5:3-8; 5:30-6:16) |

|

|

Bodmer Papyri (200 AD) – P66, P72-75 The Bodmer Papyri collection, dating from around 200 AD or earlier, contains 104 leaves. P66 includes portions of the Gospel of John (1:1-6:11, 6:35-14:26, 14:21) and is one of the earliest surviving copies of John. P72 contains the earliest known copies of Jude, 1 Peter, and 2 Peter, along with other canonical and apocryphal texts. P75 contains most of the Gospels of Luke and John and is the earliest known copy of Luke, dated between 175 and 225 AD. Pap. VIII, which includes 1 Peter and 2 Peter, was gifted to Pope Paul VI in 1969 and is now housed in the Vatican Library. The Bodmer Papyri were discovered in Egypt and consist of both codices and scrolls, mostly written on papyrus, though a few are on parchment (Pap. XVI, XIX, and XXII). These texts align with the Alexandrian text tradition, known for its early and reliable transmission of the New Testament. |

|

|

Chester Beatty Papyri (200-250 AD, dated 250 AD) – P.45, P.46, P.47 The Chester Beatty Papyri consists of three codices and contains most of the New Testament (P.45, P.46, P.47). P.45 has 30 leaves, including 2 from Matthew, 2 from John, 6 from Mark, 7 from Luke, and 13 from Acts. P.46 is the second codex, containing 86 leaves with 104 pages of Paul's epistles. P.47 is the third codex, made up of 10 leaves from Revelation. Examples from P.45 include Matthew 20:24-32; 21:13-19; 25:41-26:39; Mark 4:36-66; 9:31; 11:27-12:28; Luke 6:31-7:7; 9:26-14:33; John 4:51-5:2, 21-25; 10:7-25; 10:30-11:10, 18-36, 42-57; and Acts 4:27-17:17. |

MANUSCRIPTS

List of the Earliest "Complete" (Semi-Complete) Versions (150 – 500 AD)

- Peshitta (150 AD – oldest copy 4th Century) – Syriac – in the British Museum. Bible the eastern Churches used. It includes 22 books of the New Testament. It excludes 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, and Revelation. It also includes most of the Old Testament books, but does not include the Deuterocanonical books (Apocrypha) that are in the Septuagint (e.g., 1 and 2 Maccabees, Tobit, Judith).

- The Diatessaron (150 AD) – Syriac. The Diatessaron includes only the Four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). It is a harmony, so it doesn't include other New Testament books.

- Peshito (170 AD – oldest copy 6th Century) – Syriac – Western Churches. It includes all 27 books of the New Testament. Similar to the Peshitta, it includes most of the Old Testament, but the Deuterocanonical books are excluded.

- Curetonian Syriac (3rd Century) – Syriac. Contains portions of the New Testament, including the Gospels, Acts, and some letters, but does not include Revelation and other epistles like 2 Peter, 2 John, and 3 John. It does contain significant portions of the Old Testament, though it is incomplete and some sections are missing.

- Old Latin (Vetus Latina) (2nd – 4th Century) – Latin. Generally, they include most of the New Testament. Some manuscripts may lack parts of Hebrews, Revelation, and 2 Peter, depending on the manuscript. It includes the OT, and some Deuterocanonical books (e.g., Tobit, Judith, Maccabees) which were later excluded in the Latin Vulgate.

- Egyptian Versions Thebaic (3rd Century) – Coptic. It includes the New Testament but may exclude parts such as Revelation. It includes parts of the Old Testament.

- Egyptian Versions Memphitic (4 - 5th Century) – Coptic. It includes most of the New Testament (lacks some of the Gospels) and includes the majority of the Old Testament, based on the Septuagint (including the Deuterocanonical books).

- Gothic Version (~350 AD) – Gothic. It includes the New Testament and most of the Old Testament, based on the Greek Septuagint.

- Latin Vulgate NT (389 AD) – Latin. Jerome’s Vulgate includes all 27 books of the New Testament and the full Old Testament, based on the Hebrew Masoretic text, and includes additional books (Deuterocanonical, e.g., 1 and 2 Maccabees, Tobit, Judith).

- Ethiopic Version of the Gospels (400-500 AD) – Ge'ez (Ethiopic) “The Garima Gospels” the 4 gospels written on parchment carbon dated to this time.

- Codex Alexandrinus (425 AD) – Greek contains all 27 books of the New Testament and the Old Testament based on the Greek Septuagint.

- Codex Ephraemi (400-450 AD) – Greek. Contains most of the New Testament but excludes 2 Thessalonians and 2 John. It contains parts of the Old Testament, but not all the books. Sections are traced and parts of the text are missing.

- Codex Bezae (450 AD) – Greek and Latin. Contains only the Four Gospels and Acts.

- Codex Washingtonensis (450 AD) – Greek and Latin. It contains only the Four Gospels.

- Syriac "Philoxenian" and "Jerusalem" Versions (5th Century) – Syriac. It contain all 27 books of the New Testament. It includes most of the Old Testament, but may have textual differences compared to the later Peshitta.

- Armenian "Mesropian" Version (5th Century) – Armenian. It contains all 27 books of the New Testament and most of the Old Testament books, based on the Greek Septuagint.

- Codex Claromontanus (500’s) – Greek and Latin. It contains only the Pauline Epistles.

- Syriac Harclean Version (6th Century) – Syriac. Includes all 27 books of the New Testament and includes most of the Old Testament books.

- Codex Climaci Rescriptus (6th Century) – Syriac. Contains fragments of the Gospels, Acts, and Pauline Epistles, but it is not complete. And only a few Old Testament fragments, primarily from the Pentateuch.

- Georgian Version (6th Century) – Georgian. It contains all 27 books of the New Testament, and most of the Old Testament, based on the Greek Septuagint.

- Ethiopic Version (1300 AD) – Ge'ez (Ethiopic): The Full Bible, contains all 27 books of the New Testament. And the Old Testament is unique because it includes additional books, such as 1 Enoch and Jubilees. The Ge'ez Bible, the sacred scripture of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. It was first translated into Ge'ez around the 300 AD but the oldest surviving physical manuscripts are ~1300AD.

- Codex Sinaiticus (AD 1840 by Constantine Simonides, the lie is 330AD) – Greek. Contains all 27 books of the New Testament. And contains most of the Old Testament, based on the Septuagint, but with some parts missing (e.g., 1 and 2 Maccabees, parts of Psalms).

- Codex Vaticanus (15th Century, letters traced later, the lie is 330AD) – Greek. It contains most of the New Testament but excludes parts of Hebrews, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, and Revelation. Contains most of the Old Testament but lacks 1 and 2 Maccabees and some Psalms.

- Codex Syriacus and Codex Sinaiticus (supposed 5th Century) – Syriac Texts. Both were discovered at the Monastery of Saint Catherine by the infamous Tischendorf. He used these discoveries to bolster the Greek Text tradition while downplaying Syriac Texts that opposed his view such the legitimate Syriac "Philoxenian” (5th Century). The Guess what year he dated those that he discovered 4th-5th Century.

TWO MAIN SOURCE TEXT JOURNEY – Received Text & Critical Text

3 main schools during 250-400 AD: Rome, Antioch and Alexandria (CT). Of which Rome (Vulgate) and Antioch (Peshitta) manuscripts are the most similar and the most influential in bringing people to Jesus Christ through the centuries. The region where most of the initial evangelism through Paul took place was through Asia Minor (including Antioch) and Rome.

Received Text Path

30-95 AD – Original Autographs (New Testament writings, early Christian manuscripts)

95-150 AD – Early Greek Manuscripts (copies of originals)

120-150 AD – The Old Latin (Vetus Latina) (early Latin translations of the Bible, not fully standardized, particularly used in the West)

150-170 AD – Peshitta (Syriac Bible) (likely completed in the 2nd-3rd century, used by Eastern Churches)

150-400 AD – Papyrus Manuscripts (early New Testament fragments, including notable papyri like P52)

157 AD – The Italic Bible (early form of Old Latin used in Italy, not fully standardized)

157-400 AD – The Old Latin (Vetus Latina) (Precursor to the Latin Vulgate, 2nd-4th century; not yet the finalized version)

177 AD – The Gallic Bible (early translation into Gaul or Old French, but the full standardization came later)

310 AD – The Gothic Version of Ulfilas (Ulfilas translated the Bible into Gothic, around 350 AD)

350-1450 AD – Byzantine Text Dominant (Dominated the Eastern Roman Empire, base for the Textus Receptus)

389 AD – Latin Vulgate (final translation by Jerome, completed around 405 AD)

400 AD – Augustine Favors Byzantine Text (Augustine references the Byzantine Text type in his writings)

400 AD – The Armenian Bible (translated by Mesrop Mashtots, completed around 405 AD)

400 AD – The Old Syriac (Old Syriac versions, including the Sinaitic and Curetonian manuscripts)

349-407 AD – John Chrysostom quotes from the Byzantine Text

450 AD – The Palestinian Syriac Version (Syriac translations in Palestine, mid-5th century)

508 AD – Philoxenian Version (Syriac translation by Philoxenus of Mabbug, 5th century)

616 AD – Harclean Syriac (translated by Thomas of Harkel, 6th century)

500-1500 AD – Uncial Readings of Receptus (Uncial manuscript tradition, influencing the later Textus Receptus)

1100-1300 AD – The Latin Bible of the Waldensians (This Bible traces its roots back to the early 12th century, reflecting early reform movements)

1300-1500 AD – The Latin Bible of the Albigenses (Latin Bible used by the Albigenses, a heretical group in the 12th-13th centuries)

1382-1550 AD – The Latin Bible of the Lollards (Lollards, followers of Wycliffe, used Latin Bibles during this period)

1516 AD – Erasmus's First Edition Greek New Testament (Erasmus published this in 1516, marking the start of the Textus Receptus line)

1522 AD – Erasmus's Third Edition Published (Third edition of Erasmus' Greek New Testament, which served as a foundation for the Textus Receptus)

1522-1534 AD – Martin Luther's German Bible (Luther’s translation of the Bible was published in parts starting in 1522, completing in 1534)

1525 AD – Tyndale Version (William Tyndale's New Testament was first printed in 1526, with some earlier versions available in 1525)

1534 AD – Tyndale's Amended Version (Tyndale's later revisions of his English New Testament)

1534 AD – Colinaeus' Receptus (Greek New Testament edition by Robert Estienne in 1534)

1535 AD – Coverdale Bible (First complete English Bible translation by Miles Coverdale)

1535 AD – Lefèvre's French Bible (French translation by Jacques Lefèvre, 1535)

1537 AD – Olivetan's French Bible (The first French Protestant Bible, translated by Olivetan)

1537 AD – Matthew's Bible (Printed by John Rogers, based on Tyndale’s work)

1539 AD – The Great Bible (The first authorized English Bible, commissioned by King Henry VIII)

1541 AD – Swedish Upsala Bible (Swedish translation by Laurentius, published in 1541)

1550 AD – Stephanus Receptus (Textus Receptus) (Robert Estienne's edition of the Textus Receptus)

1550 AD – Danish Christian III Bible (The first complete Danish Bible)

1558 AD – Biestken's Dutch Work (Dutch Bible translation by Biestken, part of the early Reformation influence)

1560 AD – The Geneva Bible (The first major English translation by Protestant reformers in Geneva)

1565 AD – Theodore Beza's Receptus (Beza's critical edition of the Greek New Testament, a major influence on later translations)

1568 AD – The Bishop's Bible (An English Bible produced by the Church of England to counter the Geneva Bible)

1569 AD – Spanish Translation by Cassiodoro de Reina (The first complete Bible translation into Spanish, the Reina-Valera version)

1598 AD – Theodore Beza's Text (Beza’s final edition, which influenced the King James Version)

1602 AD – Czech Version (Kralice Bible) (Complete Czech Bible translation)

1607 AD – Diodati Italian Version (The first complete Italian Protestant Bible, by Giovanni Diodati)

1611 AD – The King James Bible with Apocrypha (First edition of the KJV with the Apocrypha included)

1613 AD – The King James Bible (Apocrypha Removed) (The standard edition of the KJV, Apocrypha omitted in later editions)

1769 AD – 4th Update of the English Language in the King James Bible (The standardized revision of the King James Bible, primarily for spelling and language updates)

Critical Text Path

30-95 AD – Original Autographs (New Testament writings composed)

200-331 AD – Papyrus Manuscripts (Early New Testament manuscripts, including important papyri like P52)

331 AD – Codex Sinaiticus & Codex Vaticanus (Foundational Greek manuscripts for Critical Text. This date was fabricated. Sinaiticus fabricated document by Simonides for Russian Tsar. Vaticanus 15th Century manuscript)

425 AD – Codex Alexandrinus (An important manuscript for the Alexandrian text-type, dating to the 5th century)

1516 AD – Erasmus' Greek New Testament (The first printed Greek New Testament. Erasmus’ work laid the foundation for the Textus Receptus, a precursor to modern critical texts)

1881 AD – Westcott & Hort's Critical Text (Combined Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, forming the modern Critical Text foundation. This text has influenced most modern Bible translations)

1901 AD – American Standard Version (ASV) (The first major English translation based on the Critical Text)

20th Century – Nestle-Aland & UBS Texts (Modern Critical Texts, with regular updates in collaboration with scholars from the United Bible Societies)

VARIOUS SOURCE TEXT

CRITICAL TEXT

The Critical Text (AD 1881 Westcott and Hort Text) Text is used as the source for most modern English translations, such as, NASB, NIV, NLT, NET, RSV, ESV etc. The Critical Text (Alexandrian Text) is a source text of the New Testament, which was completed in 1881 AD by Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort. They were scholars of Cambridge university. This text is mainly based on just two primary source manuscripts: the Vaticanus (also known as "B") and the Sinaiticus (also known as "Aleph"). Codex Alexandrinus (425AD) is a secondary source and a minor contributor.

The Sinaiticus was discovered by Tischendorf in 1859 at St. Catherine’s Monastery. He alleged that it was from the 4th century. Tischendorf's discovery of the Sinaiticus also contributed to the eventual decision by the Vatican to make the Vaticanus more accessible to scholars. The Vaticanus had been housed in the Vatican since the 15th century. Scholars also alleged that the Vaticanus is a 4th-century work, and thus, these two source texts were used in the compilation of the critical text.

The dating and authenticity of the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus manuscripts are unproven and highly questionable. It is more likely that Sinaiticus was fabricated in the 19th century, and Vaticanus in the 15th century.

The Validity of the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus Text

- Sinaiticus has approximately 15,000 corrections, making it the most corrected of all Greek manuscripts.

- Vaticanus, a 15th-century work, was not dated to the 4th century until after the discovery of Sinaiticus. Additionally, a later scribe went over certain parts of the original text, obscuring it.

- It was a Catholic-inspired compilation created as a "Counter-Reformation" by the Jesuits.

- Tischendorf stole Sinaiticus from St. Catherine’s Monastery without permission.

- Constantine Simonides, a respected paleographer, claimed he was commissioned by Tsar Nicholas I to compile the text at St. Catherine’s in the 1840s, working with two other Greeks.

- Neither Sinaiticus nor Vaticanus has scientific proof of being from the 4th century. Scholars based the 4th-century dating on Simonides' fabricated work.

- Monks and many others testified, confirming Simonides' claim. The authorities didn’t want to hear them, and the media worked to suppress and discredit Simonides.

- Despite having his work stolen by Tischendorf, Simonides gained nothing except the pursuit of what was right and respect for the manuscripts. He sacrificed his credibility to defend his work.

The majority of the 5,300+ Greek fragments and manuscripts agree with the RT. Some scholars have argued that errors were passed down through the years, but RT scholars would counter that those verses are found in earlier manuscripts, such as Syriac, Aramaic, Latin, quotes from early church leaders, and some Greek fragments.

The Peshitta text, which at that time, was considered the oldest manuscript available contradicted the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus. However, before the texts were established, it was interesting that Dr. Brooke Foss Westcott, in The New Testament Canon (1855), who later supported the Alexandrian text, said that he saw "no reason to desert the opinion which has obtained the sanction of the most competent scholars that the formation of the Peshitta Syriac should be fixed within the first half of the second century. The very obscurity which hangs over its origin is proof of its venerable age, because it shows that it grew up spontaneously among Christian congregations. Had it been a work of a later date, of the 3rd or 4th century, it is scarcely possible that its history should be so uncertain as it is." BUT later after his work of the Critical Text, in Introduction to the New Testament Greek (1882), he changed his view of the Peshitta after seeing how it often agreed with the Byzantine texts and contradicted the Alexandrian texts (Critical Text) he had supported. He then concluded that the Peshitta must have been a revision of the Old Syriac, a position that many today continue to mistakenly teach and a quest to find Syriac text that matched the Alexandrian Text. Those that were found were dubbed, earlier Syriac text.

The key difference between the Received Text (RT) and the Critical Text (CT) is approximately 3,000 Greek words. These missing words are scattered throughout the New Testament. Therefore, both texts cannot be true: either the words were added to the original or the CT compilation and its sources are corrupt. When compared to the RT, the following verses are missing from the CT: Matthew 6:13; 12:47; 17:21; 18:11; 23:14; Mark 7:16; 9:44, 46; 11:26; 15:28; 16:9-20; Luke 9:55-56; 17:36; 22:43-44; 23:17; John 5:3-4; 7:53-8:11; Acts 8:37; 15:34; 24:6-8; 28:29; Romans 16:24; 1 Corinthians 15:47; 2 Corinthians 13:14; Galatians 4:7; Ephesians 3:9; Colossians 1:2, etc.

Therefore, are these words quoted by other leaders, found in other early fragments, or present in other ancient texts such as Aramaic or Latin? The answer is yes. However, for those who want to validate using the English translations, they can refer to the KJV (RT, AD 1522-1598), Wycliffe (Latin Vulgate, 12th Century), NET/ESV (CT, AD 1881 – refer to margin notes NU), Murdock (Peshito Aramaic, 15th-17th Century, based on an older version), and Lamsa (Peshitta Aramaic, 5th Century).

BYZANTINE TEXT

Many consider the Roman Emperor Constantine I (reigned 306–337) to be the first Byzantine Emperor. The earliest Church Father known to witness to a Byzantine text-type in his New Testament quotations is John Chrysostom (349–407 AD). The Byzantine text has its origins in Europe and Asia Minor, particularly in places like Antioch, Rome, Corinth, and Ephesus. Fragments found in these regions are typically of the Byzantine text-type. The Byzantine text was originally written in uncials (uppercase letters in Koine Greek) and later transitioned to minuscule (lowercase letters in Koine Greek) starting in the 9th century.

One of the earliest surviving manuscripts of the Byzantine text is Codex Alexandrinus (5th century). While the Gospels in this specific manuscript are closer to the Byzantine text-type, the rest of the New Testament (such as the Acts and Epistles) follows the Alexandrian text-type.

The Byzantine text-type has the largest number of surviving manuscripts from 350 to 1500 AD. Consequently, it is often referred to as the Majority Text. The Byzantine Text was used to compile the Received Text (1512), also known as the Textus Receptus.

NT BYZANTINE TEXT THROUGH THE CENTURIES

- Codex Alexandrinus (~400–440 AD). Gospels, Acts, Epistles (includes most of the New Testament)

- Codex Ephraemi (~400–450 AD). Most of the New Testament (except 2 Thessalonians and 2 John)

- Codex Bobbiensis (~400–450 AD). Pauline Epistles

- Codex Washingtonianus (~400–450 AD) Matthew 1-28, Luke 8:13–24:53

- Codex Guelferbytanus B (~400–450 AD). Luke–John

- Uncial 061 (~400–450 AD). 1 Timothy 3:15-16; 4:1-3; 6:2-8

- Codex Bezae (~450 AD). Four Gospels, Acts (Greek and Latin, Western text-type)

- Codex Claromontanus (~500 AD). Pauline Epistles (with Western text-type but includes Byzantine readings)

- Codex Basilensis (~800 AD). Gospels

- Codex Sangallensis (~900 AD) Gospels (partial)

- Codex Regius (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Boreelianus (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Seidelianus I (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Seidelianus II (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Angelicus (~900 AD) Acts and Epistles

- Codex Mosquensis II (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Macedoniensis (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Koridethi (~900 AD) Gospels (except Mark)

- Codex Augiensis (~900 AD) Epistles

- Minuscule 33 (~900 AD) New Testament (except Mark)

- Minuscule 892 (~900 AD) Gospels

- Codex Vaticanus 354 (~949 AD) Gospels

- Minuscule 1241 (~1200 AD) Acts

- Minuscule 1424 (~900–1000 AD) New Testament (except Mark, includes Revelation)

In addition, the way they agreed on which text stays or ignored is dubious, and similar to Westcott-Hort method of the Critical Text. Even though, it isn’t perfect it is closer to the Received Text (RT) than the Alexandrian text (Critical Text - CT), except for the Book of Revelation.

Majority Text

It is important to distinguish between the Majority Text, which refers to the large number of Byzantine manuscripts (around 5,300), and the Majority Text compiled in the 20th century by Hodges and Farstad (1982), which is based on a smaller subset of approximately 400 Byzantine manuscripts (414). Today when some refers to the Majority Text, they are either referring to the work done by Hodges & Farstad (1982) OR Robinson & Pierpont (1991). It is not the entirety of the Byzantine Text. The English translation of Hodges & Farstad MT is the EMTV. The English translation (EMTV) italicizes words that the English translation adds for readability. The English translation of Robinson & Pierpont MT is the MLV. There are about 400 differences between these two “Majority Text” – most of them John 7 & 8 (of the Adulteress) and the Book of Revelation. Here are a few: Matthew 26:11; Luke 7:6; 14:24; John 8:7, 9-10; Rom. 12:2; Col. 1:14; Heb. 10:17; Rev. 2:7; 4:4;7;11; 5:8; 11:6; 13:1; 18, etc. Hodges & Farstad Majority Text (MT) matches Received Text (RT) more than Robinson & Pierpont.

Received Text – Textus Receptus

Erasmus, Stephanus, Beza and the Elzevir brothers formed the text known as Textus Receptus (RT). The most notable editor of all was Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536AD). Today the term Textus Receptus is used generically to apply to all editions of the Greek NT which follow the printed editions of Desiderius Erasmus. He was upset with the inaccuracy that crept into the Vulgate Bible over the years (copying errors and mistranslations based on human interpretation).

Because he was a Roman Catholic scholar he re-translated the NT into Latin and prepared an edition of the Greek to be printed beside his Latin version to demonstrate the text from which his Latin came (published in 1512-1513). Out of the thousands of minuscule manuscripts, he used a few he respected: Below is a list of the seven Byzantine manuscripts used of Erasmus in his 1516 edition. Of these, the only manuscript Erasmus had for Revelation missed Rev. 22:16-21, which is believed to be retranslated from the Latin. But the other editions, he could have used other manuscripts.

A minuscule is a type of Greek manuscript of the New Testament written in lowercase letters. It refers to a specific script style used in manuscripts, typically from the 9th century onward. These manuscripts are distinct from earlier uncial manuscripts, which were written in uppercase letters.

Source Text - Erasmus Used

|

Minuscule 1 (1eap) |

9-10th Century |

Entire NT (except Revelation) |

|

Minuscule 1 (1rk) |

10th Century |

NT (used for Revelation) |

|

Minuscule 2 (2e) |

10th Century |

Gospels |

|

Minuscule 2 (2ap) |

11th Century |

Only Epistles and Acts |

|

Minuscule 4 (4ap) |

11th Century |

Pauline Epistles |

|

Minuscule 7 (7p) |

11th Century |

Epistles |

|

Minuscule 817 |

12th Century |

Gospels |

In addition to Erasmus’ work, Source Text - Stephanus used

|

Minuscule 60 |

10th Century |

Gospel of Luke |

|

Minuscule 629 |

12th Century |

Gospels |

In addition to Erasmus’ & Stephanus work, Source Text - Beza used

|

Codex Bezae (D) |

5th Century |

Gospels and Acts |

|

Minuscule 33 |

9th Century |

Gospels |

|

Minuscule 120 |

11th Century |

Pauline Epistles |

There are 6 Received Text but 3 MAIN Source Texts (bold)

- NT Complutensian Polyglot Greek Version (1520) – Greek, Latin and Hebrew.

- Erasmus published five editions (1516, 1519, 1522, 1527, 1535) – Tyndale, Matthew, Coverdale used.

- Robert Stephanus published four (1546, 1549, 1550, 1551) – Geneva 1560

- Theodore Beza published at least four independent editions (1556, 1582, 1588-89, 1598) – Geneva 1587 & 99

- The Elziver family printed two editions (1624, 1633).

- Scrivener’s edition was an attempt to reconstruct the Textus Receptus – thus not part of the original Received Text.

Major Differences across the Received Text

|

RECEIVED TEXT |

ERASMUS |

STEPHANUS |

BEZA |

|

Early Manuscript supports it: Peshitta - Lamsa (Pa), Peshitto -Murdock (Po), Vulgate – Wycliffe (V) |

9V6Po5Pa |

5V5Pa5Po |

5V7Pa8Po |

|

Matt 2:11 |

And went into the house and found… V |

And went into the house and found… V |

And went into the house and saw… PaPo |

|

Matt 10:10 |

Staff VPaPo |

Staff VPaPo |

Staves

|

|

Mark 9:40 |

..not against you is on your side VPaPo |

…not against us is on our side |

…not against us is on our side |

|

Luke 2:22 |

their purification PaPo |

their purification PaPo |

her purification |

|

Luke 17:36 |

Omitted (V) |

1st 3 editions Omit, 4th Includes it (PaPo) |

PaPo |

|

John 1:28 |

Bethabara beyond Jordan |

1st and 2nd editions of Stephanus have “Bethany beyond Jordan.” (PaPoV) 3rd and 4th editions of Stephanus have “Bethabara beyond Jordan |

Bethabara beyond Jordan |

|

John 16:33? |

have tribulation (V) |

have tribulation (V) |

shall have tribulation (PaPo) |

|

Romans 8:11 |

because of His Spirit that dwelleth in you |

because of His Spirit that dwelleth in you |

by His Spirit that dwelleth in you |

|

Romans 12:11 |

1st Edition - serving the Lord (VPaPo) , last 4 editions serving the time |

serving the time |

serving the Lord (VPaPo) |

|

1 Timothy 1:4 |

godly edifying (VPo) |

dispensation of God |

godly edifying (VPo) |

|

Hebrews 9:1 |

Has “tabernacle.” (VPaPo) |

first tabernacle |

omit “tabernacle.” (VPaPo) |

|

James 2:18 |

by thy works |

by thy works |

1st Edition - by thy works. Last 4 editions - without thy works VPaPo |

|

2 Peter 2:9 |

Temptation V |

Temptation V |

Temptations

|

|

1 John 2:23 - but he that acknowledgeth the Sonne, hath the Father also. |

Omitted portion |

Omitted portion |

Included VPaPo |

|

Revelation 11:1 |

Omit - “Angel stood” |

“Angel stood” |

“Angel stood” |

|

Revelation 16:5 |

And Holy VPaPo |

And Holy VPaPo |

And shalt be |

Which is the most accurate RT based on early manuscript comparisons?

Beza is the most accurate with Syriac but Erasmus most accurate with Latin Vulgate.

What Received Text does the King James (KJV) use?

The KJV primarily used the Beza Received Text, followed by Erasmus and then Stephanus. Based on the variations identified by Scrivener, it appears that the KJV relied mainly on Beza (approximately 45%), Erasmus (approximately 32%), and Stephanus (approximately 23%). However, the KJV also includes readings that are not found in the Received Text, such as Mark 15:3, "but he answered nothing," and John 8:6, "as though he heard them not."

How do you know which Received Text you have?

Use two verses: 1 John 2:23 and Luke 17:36. If 1 John 2:23 reads, “but he that acknowledgeth the Son hath the Father also,” then it follows Beza’s or later editions. If this phrase is omitted, then it aligns with Stephanus or Erasmus. For Luke 17:36, if it includes the phrase “two shall be in the field…” then it follows Stephanus. If the phrase is missing, then it aligns with Erasmus.

FEW MAJOR DIFFERENCES BETWEEN RT & CT

A. MARK 16:9-20

Earliest Manuscripts that include this passage:

- Peshitta (150 AD – oldest copy 4th Century)

- Old Latin (2nd-4th Century) (Vetus Latina) translations, used in the early Western church.

- The Gothic Version (~350 AD), translated by Ulfilas.

- Latin Vulgate (Late 4th Century) by Jerome.

- Codex Bezae (5th Century): A Greek-Latin manuscript.

- Codex Alexandrinus (5th Century): Used in the compilation of the 19th-century Critical Text by Westcott and Hort – but not weighted as much as erroneous Sinaiticus and Vaticanus.

- The Philoxenian Syriac (5th Century) – prior to the 19th Century (prior to CT influence), this was dates 4th Century. This

- Syriac Harclean Version (early 6th Century)

Church Leaders:

- Papias (AD 100) – "By Eusebius, Hist. Ecc. 3, 39" Quoted verse 18: "They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover."

- Diatessaron (AD 150 – earliest copy ~380 AD), a harmony of the Gospels include specifics only found in Mark 16:9-20 e.g. Appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene Mark 16:9, the great commission in Mark 16:15-16, signs follow those who believe (Mark 16:17-18).

- Justin Martyr (AD 151) – "Apol. I. c. 45" Quoted verse 20: "And they went forth, and preached everywhere, the Lord working with them, and confirming the word with signs following. Amen."

- Irenaeus (AD 180) – "Adv. Hoer. lib. iii. c. x." Quoted verse 19: "So then after the Lord had spoken unto them, he was received up into heaven, and sat on the right hand of God."

- Hippolytus (AD 190–227) – "Lagarde's ed., 1858, p. 74" Quoted verses 17-19: "And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; they shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover. So then after the Lord had spoken unto them, he was received up into heaven, and sat on the right hand of God."

- The Acta Pilati – “Acts of Pilate” (2nd Century) – "Tischendorf's ed., 1853, p. 243, 351" Quoted verses 15-18: "And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature. He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned. And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; they shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover."

- Vincentius (AD 256) – Quoted at the 7th Council of Carthage under Cyprian

Quoted verses 15-16: "And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature. He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned." - The Apostolical Constitutions (3rd or 4th Centuries) Quoted verses 16-18: "He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned. And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; they shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover."

- Eusebius (AD 325) – Discusses these verses as quoted by Marinus from a lost part of his history. Eusebius discussed verses 17-20, focusing on the signs that follow believers and their connection to the apostles' ministry after Christ’s ascension.

- Ambrose of Milan (AD 374-397). Quoted multiple verses from Mark 16.

- Jerome (AD 331-420). Acknowledges some manuscripts lack the passage but still included it in the Latin Vulgate.

- Augustine (AD 395-430) Discusses the verses as being part of the work of Mark and publicly read in churches.

- Chrysostom (AD 400). Refers to verse 9, states verses 19-20 as "the end of the Gospel."

- Victor of Antioch (AD 425) Referred to many manuscripts containing the verses.

- Nestorius (AD 430) Quoted verse 20.

- Cyril of Alexandria (AD 430) Accepted the verses.

Mark 16:9-20 is included in the Peshitta (oldest copy 4th Century), confirmed by its usage in the Eastern Orthodox Church in the 6th century, as well as in the Old Latin Vulgate (2nd –4th century). The earliest Greek texts that include it are the Codex Bezae and Alexandrinus (5th Century). Thus, they are also in Received Text, which is based on 9th –10th century copies of Koine Greek. They were quoted and affirmed by the earliest Church leaders (2nd - 5th century). Therefore, it can be concluded that the Critical Text is not only in error but misleading and flawed. Keep in mind that the Codex Alexandrinus, which is the only legitimate ancient text used in the compilation of the Critical Text, includes Mark 16:9-20. The Sinaiticus and Vaticanus are flawed.

B. JOHN 7:53-8:11

Earliest Manuscripts that Include This Passage:

- Old Latin (2nd-4th Century) (Vetus Latina) translations, used in the early Western church.

- The Gothic Version (~350 AD), translated by Ulfilas.

- Latin Vulgate (Late 4th Century) by Jerome.

- Codex Bezae (5th Century): A Greek-Latin manuscript.

- Codex Alexandrinus (5th Century): Used in the compilation of the 19th-century Critical Text by Westcott and Hort – but not weighted as much as erroneous Sinaiticus and Vaticanus.

- The Philoxenian Syriac (5th Century).

- Syriac Harclean Version (6th Century).

Church Leaders Who Acknowledge the Passage:

- Tertullian (AD 155-240), in his work "Against the Jews" (Chapter 9), Tertullian alludes to the story of the woman caught in adultery, recognizing its acceptance in some circles within the early Christian tradition. Though not directly commenting on its canonicity, his reference shows the passage was known and accepted in the early Church.

- Origen (AD 185-245), in his Commentary on the Gospel of John, specifically in Book 14, Chapter 25, while he expresses caution about its authenticity, he does not outright reject it and states, “But this section of the Gospel, the story of the adulterous woman, is not found in the most ancient copies of the Gospel.” Keep in mind Origen lived in Alexandria, Egypt, where Gnosticism had a significant presence.

- Ambrose of Milan (AD 340–397): In Exameron (Book VI, 17), Ambrose refers to the woman caught in adultery, indicating its acceptance in the Western tradition.

- Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430): In De adult. et lib. conjug (On the Good of Marriage and on the Good of Widowhood, 2.8), Augustine defends its inclusion. He notes that while some manuscripts omit the passage, it was widely accepted.

- Jerome (AD 347–420): In his Prologue to the Gospel of John, Jerome acknowledges that some manuscripts lack the passage, but he chose to include it in the Vulgate.

- Cyril of Alexandria (AD 376–444): In his Commentary on the Gospel of John (6.37), Cyril indicates the passage was part of the Alexandrian tradition, even if not universally included.

C. MATTHEW 6:13 “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen.”

Earliest Manuscripts that Include This Passage:

- Peshitta (150 AD – oldest copy 4th Century) "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Old Latin (2nd-4th Century) (Vetus Latina) "For thine is the power and the glory forever"

- Curetonian Syriac (3rd Century) "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Gothic Version (~350 AD), translated by Ulfilas "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Latin Vulgate (Late 4th Century). For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Codex Alexandrinus (5th Century) – Koine Greek "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Early Coptic Versions (4th-5th Century): Early Sahidic and Bohairic Coptic manuscripts "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Codex Bezae (5th Century): This Greek-Latin manuscript includes the full: "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- The Philoxenian Syriac (5th Century).

- Syriac Harclean Version (6th Century).

Church Leaders Who Acknowledge the Passage:

- The Didache (AD 70-130 – earliest copy ~400AD) "For thine is the power and the glory forever."

- Diatessaron (AD 150 – earliest copy ~380 AD), harmony of the four Gospels by Tatian "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Hippolytus of Rome (AD 170–235) "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Ambrose of Milan (AD. 340–397) Exameron (Book VI, 17), he refers to the doxology in the context of the Lord's Prayer. The doxology, "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen"

- Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430) References the doxology in "Expositions on the Psalms" (Psalm 143).

- The Apostolic Constitutions (AD 380) "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- John Chrysostom (AD 400 AD) "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

- Opus Imperfectum in Matthaeum (AD 400s) "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen."

D: 1 JOHN 5:7 “the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.”

Earliest Manuscripts that Include This Passage:

- The Old Latin (Vetus Latina AD 150-200 AD), although not uniform across all manuscripts, saw the passage become more consistently included in later versions.

- Latin Vulgate (Late 4th Century). Jerome has a change from the Old Latin from “Word” to “Son”, therefore “the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.”

- Codex Bezae (5th Century) – a Greek-Latin diglot manuscript, where the Latin side preserves the passage, but the Greek side does not.

The Comma Johanneum does appear in a few later Greek manuscripts, some examples include:

- Minuscule 61 (12th century)

- Minuscule 629 (12th century)

- Minuscule 2886 (14th century)

- Minuscule 1830 (15th century)

Textus Receptus: 3 main Received Text compilations in 1500-1600 (1st Erasmus - Tyndale, 2nd Stephanus - Geneva, 3rd Beza - ~KJV), each has about 5-6 editions (~17 editions). 1 John 5:7 is in all of them except Erasmus' first 2 editions. The question is why? These were the manuscripts he had at the time. Then he found another Greek manuscript that had it in, thus he updated the text in his 3rd edition.

Church Leaders Who Acknowledge the Passage (AD 200-500):

- Cyprian (AD 200-258), in his work Treatises, The Ante-Nicene Christian Library (5:423), Cyprian quotes 1 John 5:7, "...and again it is written of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, 'And these three are one.'" It is likely that Cyprian used at older Latin, which was in circulation before Jerome's Vulgate. It is possible that the original Greek text was altered in the Latin from "Word" to "Son."

- The Gothic Version (c. 350 AD). The Gothic Bible, translated by Ulfilas includes "For there are three who bear witness in heaven: the Father, and the Word, and the Spirit." But doesn’t include the three these three are one"

- Priscillian or Bishop Instantius (AD 380) in Liber Apologeticus, later charged with Manichaeism. The text says: "...as John says, 'And there are three which give testimony on earth: the water, the flesh, and the blood, and these three are in one. And there are three which give testimony in heaven: the Father, the Word, and the Spirit, and these three are one in Christ Jesus.'"

- Idacius Clarus or Vigilius Tapsensis (AD 450) in Contra Varimadum Arianum "John the Evangelist, in his Epistle to the Parthians (i.e., 1 John), says there are three who give testimony on earth: the water, the blood, and the flesh, and these three are in us; and there are three who give testimony in heaven: the Father, the Word, and the Spirit, and these three are one."

The three earthly witnesses are referred to as "flesh" rather than the usual "Spirit".

RECEIVED TEXT DIFFERENCES WITH VULGATE

Work in progress---

Matthew 4:17 – "Repent" in RT, and "Do penance" in Vulgate

Matthew 6:13 – Includes "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory" in RT, but omitted in Vulgate

Matthew 18:11 – "For the Son of Man is come to save that which was lost" in RT, but omitted in Vulgate

Luke 1:28 – "Has found favour with God" in RT, and "Full of grace" in Vulgate

Luke 10:1 – "Seventy" in RT, and "Seventy-Two" in Vulgate

John 1:18 – "Only begotten Son" in RT, and "Only begotten God" in Vulgate

John 3:13 – "No man hath ascended up to heaven" in RT, omitted in Vulgate

John 5:4 – Included in RT, omitted in Vulgate

John 10:30 – "I and my Father are one" in RT vs. "I and the Father are one" in Vulgate.

John 14:14 – "If ye shall ask anything in my name, I will do it" in RT vs. "If ye ask anything in my name, I will do it" in Vulgate.

John 16:16 – "A little while, and ye shall not see me: and again, a little while, and ye shall see me" in RT vs. "In a little while, and ye shall not see me: and again, in a little while, ye shall see me" in Vulgate.

1 Timothy 1:17 – "Wise" in RT, but no "wise" in Vulgate

Jude 1:25 – "Wise" in RT, but no "wise" in Vulgate

1 John 5:7-8 – Includes "The Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost" in RT, but not in Vulgate (Comma Johanneum)

Acts 8:37 – Includes "If thou believest with all thine heart" in RT, but omitted in Vulgate

Mark 16:9-20 – Longer ending included in both RT and Vulgate, but debated in early manuscripts

Revelation 1:11 – "The first and the last" in RT, and "Principium et finis" in Vulgate

Revelation 5:9 – "Us" in RT, omitted in Vulgate